One element of the Battle of Fort Donelson which should surprise modern readers is the fact that the most senior Confederate officer present, John B. Floyd, elected to escape rather than share the fate of the soldiers under his command.

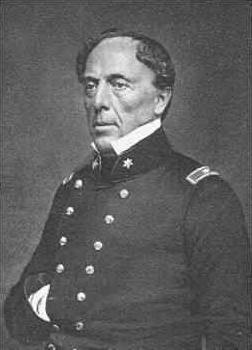

Brigadier General John B. Floyd was fifty-five years old in February 1862. Prior to the Civil War, he had been a lawyer and politician in Virginia, serving as governor of the state (1849-1852) and as the Federal Secretary of War (1857-1860) where he succeeded the future president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis. He was appointed a colonel in the Virginia Provisional army in 1861 and was promoted to brigadier general when the state’s forces were accepted into Confederate service. He arrived at Fort Donelson on February 13th with his brigade of four regiments of infantry from western Virginia (36th VA, 50thVA, 51st VA, 56th VA). As the senior officer present based on date of rank, he assumed overall command of the fort in spite of the fact that he lacked military experience and relied heavily on Generals Pillow and Buckner to direct operations.

Brigadier General John B. Floyd was fifty-five years old in February 1862. Prior to the Civil War, he had been a lawyer and politician in Virginia, serving as governor of the state (1849-1852) and as the Federal Secretary of War (1857-1860) where he succeeded the future president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis. He was appointed a colonel in the Virginia Provisional army in 1861 and was promoted to brigadier general when the state’s forces were accepted into Confederate service. He arrived at Fort Donelson on February 13th with his brigade of four regiments of infantry from western Virginia (36th VA, 50thVA, 51st VA, 56th VA). As the senior officer present based on date of rank, he assumed overall command of the fort in spite of the fact that he lacked military experience and relied heavily on Generals Pillow and Buckner to direct operations.

During the council of war which followed the failed Confederate attempt to break the siege on February 15th, the three general officers at Donelson decided among themselves that their mission to delay Grant’s advance on Nashville had been achieved and, as General Buckner put it: “It would be wrong to subject the army to a virtual massacre when no good could result from the sacrifice.” Immediately, Colonel Bedford Forrest who commanded all of the garrison’s cavalry announced that he would not surrender his command. Upon hearing this, Floyd appears to have reconsidered his personal position.

As the Secretary of War in the period immediately prior to the outbreak of the war, Floyd was under suspicion in the North for moving substantial numbers of muskets and cannons from the northern states into armories throughout the southern states. It is more likely that, rather than as a preparation for secession, the transfers were made due to the fear of slave uprisings following John Brown’s raid on the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. Following Forrest’s announcement, Floyd announced that he would evacuate his four regiments using steamboats scheduled to bring reinforcements the following morning.

Floyd must certainly have been influenced in this decision not only by the announcement that Bedford Forrest would lead an escape by the cavalry, but also by the fact that this surrender would be only the second time when Confederate general officers would be surrendered and it wasn’t clear if they would be treated as legitimate prisoners-of-war or as outright traitors to the Federal government. Aside from General Buckner (a career army officer who had formally resigned his commission), Floyd would be the first general officer captured who had sworn an oath of allegiance to the Federal government. The possibility of being hung as a traitor must have played on his mind. In addition, there existed the possibility that a closed Federal indictment against him for malfeasance while Secretary of War could be reopened.

In the event, Floyd moved his brigade to the landing in the early morning of February 16th and, after reinforcements from Nashville came ashore, Floyd loaded his Virginians aboard the two boats as the sun rose, leaving the men of the 20th Mississippi behind as the rearguard. It appears that only two of his four Virginia regiments loaded successfully, leaving the 50th and 56th Virginia regiments behind to be captured.

The four Virginia regiments had been recruited in southwestern counties of modern Virginia. After their escape, the 36th and 51st returned to Virginia and participated in operations in the Shenandoah valley and the mountain country between the upper valley and Knoxville, TN. The captured 50th and 56th Virginia were reorganized following their exchange from captivity and fought in the Army of Northern Virginia from 1862 until the end of the war.

Floyd was relieved of command of his brigade by President Davis in March, but was appointed a major-general of state troops by the governor of Virginia. He became ill shortly afterwards and played no further part in the war. He died at home in August 1863.

Union General W.H.L. Wallace summarized Floyd’s post-battle reputation: “Without loss of time the general (Floyd) hastened to the river, embarked with his Virginians, and at an early hour cast loose from the shore, and in good time, and safely, he reached Nashville. He never satisfactorily explained upon what principles he appropriated all the transportation on to the use of his particular command”.