We continue the discussion of Confederate generals at Fort Donelson to escape the surrender with the second-in-command, Gideon J. Pillow, who had himself and his chief-of-staff rowed across the Cumberland River after being placed in command by the fleeing John B. Floyd.

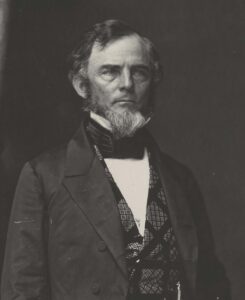

Like Floyd, Brigadier General Gideon Johnston Pillow was fifty-five years old in February, 1862. Prior to the Civil War, he practiced law in Columbia Tennessee with partner and future president James K. Polk. He served as a brigadier general in the Tennessee militia during the Indian removals of the 1830s, but saw no combat.

Like Floyd, Brigadier General Gideon Johnston Pillow was fifty-five years old in February, 1862. Prior to the Civil War, he practiced law in Columbia Tennessee with partner and future president James K. Polk. He served as a brigadier general in the Tennessee militia during the Indian removals of the 1830s, but saw no combat.

During the Mexican-American War, Pillow joined the United States Army as a brigadier general in July 1846. His former law partner, now President of the United States, promoted him to major general on April 13, 1847.

Although he was wounded twice during the war, his mistake at the Battle of Cerro Gordo caused unnecessary American casualties. Against orders, he used an exposed approach to attack the Mexican lines in full view of several Mexican batteries, instead of advancing down a gully out of sight of the Mexican lines. The Mexican army drove Pillow’s column back. Fortunately, the day was won by the Americans on other parts of the field. After recovering from a wound to his right arm, his next action was in the final attack on Mexico City. The American commanding general, Winfield Scott, assigned Pillow’s division to clear Mexican troops from the fortified town of Chapultepec which controlled access to the causeways into the city. Here Pillow performed well and received a wound in his leg.

Less than a month after the battles of Contreras and Churubusco, the New Orleans Delta published an anonymous letter that wrongfully credited Pillow for those victories. In fact, Pillow was the anonymous author using the pseudonym ‘Leonides’.

At Contreras, Pillow was the sole division commander on the field. However, it was Winfield Scott’s plan that led to the victory after Brigadier General Persifor Smith, on his own initiative, took command of his own and two other brigades and led them on a night march that flanked the Mexican position.

Pillow was but one of four division commanders with troops engaged at Churubusco, where repeated attacks by troops from all divisions eventually wore down the garrison.

During the subsequent scandal over the ‘Leonides’ letter, Pillow escaped punishment by bribing another officer to claim credit for being the author and through the intervention of his former law partner. Polk recalled Scott to Washington, claiming that Pillow was being “greatly persecuted”.

In his memoirs, Scott wrote that Pillow was “amiable and possessed of some acuteness, but the only person I have ever known who was wholly indifferent in the choice between truth and falsehood, honesty and dishonesty: ever as ready to attain an end by the one as the other, and habitually boastful of acts of cleverness at the total sacrifice of moral character.” It appears that this sentiment was shared by a majority of the professional soldiers who fought in Scott’s army.

Pillow’s further Civil War experience follows in Part 2.