Early Life

Lloyd Tilghman was born in “Rich Neck Manor”, Claiborne, Maryland, great-grandson of a Maryland representative to the Continental Congress and grand-nephew of a man who had served on George Washington’s staff during the American Revolution. He attended the United States Military Academy and graduated near the bottom of his class in 1836. He was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 1st U.S. Dragoons, but resigned his commission after three months. [ed. You could do that in 1836 because of the scarcity of trained engineers in the civil sector.]

He worked as an engineer from 1837 to 1845, before rejoining the Army during the War with Mexico.

He arrived in Corpus Christi as a sutler in September 1845, but when the army discovered that he had been a lieutenant in the Dragoons and graduated from West Point, General David Twiggs made him aide de camp of the 2nd U.S. Dragoons. Tilghman spent most of the war designing and building fortifications and would later become the captain of the Maryland and District of Columbia Volunteer Artillery, operating six light artillery pieces.

Following the war, Tilghman resumed his profession as an engineer of railroads. In 1852, he moved to Paducah, KY, with his wife Augusta Murray Boyd, and their sons and daughters to work for the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. Ironically, he took up residence in a house across the street from the hotel which would become the headquarters of the Union garrison in 1862. In Harper’s Rescue, the Tilghman house becomes the residence of the staff officers of the Union garrison.

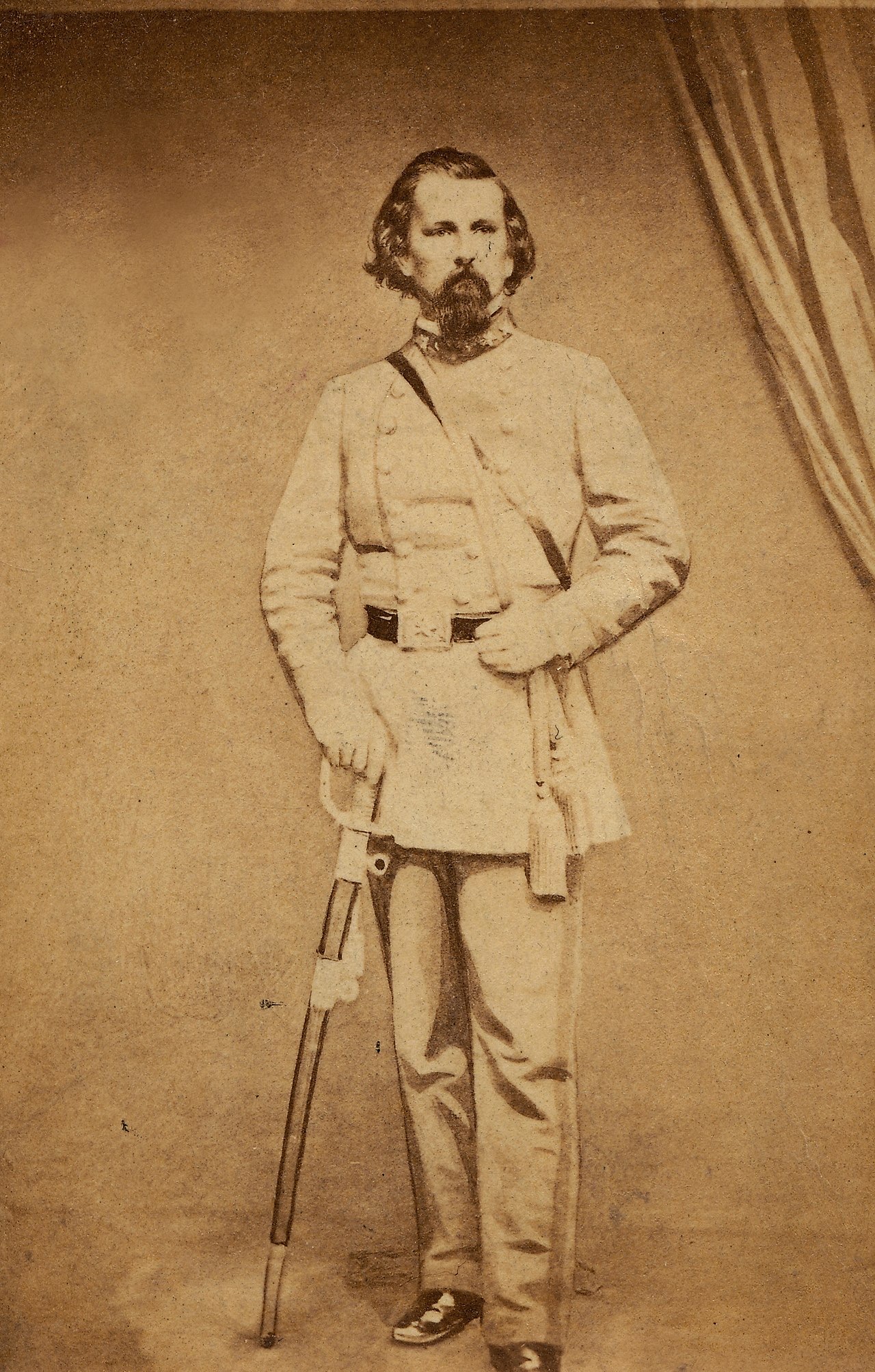

Civil War

Simon Bolivar Buckner, then in command of all Confederate troops in Kentucky, commissioned Tilghman as colonel of the 3rd Kentucky Infantry [CSA] on July 5, 1861. Tilghman faced an impossible task: to arm and clothe his unit without help from the state, which held the position that Kentucky’s neutrality prevented it from supplying arms or accoutrements to men enlisting to fight for either side.

He became a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army on October 18, after Kentucky troops were accepted into the Confederate Army.

When General Albert Sidney Johnston was looking for an officer to create defensive positions on the vulnerable Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, he was unaware of Tilghman’s presence in his department and another officer was selected. However, the Richmond government pointed out Tilghman’s engineering background and Johnston appointed him he to the task.

General Daniel S. Donelson, another West Point graduate, but more a politician than an engineer, had already marked the sites for Forts Henry and Donelson. Tilghman was placed in command and ordered to construct them. The geographic placement of Fort Henry was extremely poor, sited on a floodplain of the Tennessee River, but Tilghman did not object to its location until it was too late. Afterward, he wrote bitterly in his report that Fort Henry was in a “wretched military position … The history of military engineering records no parallel to this case.” [ed. Read about the Battle for Fort Henry at the Harper’s Donelson page of this website.]

Construction of both forts, as well as the smaller Fort Heiman across the Tennessee River from Fort Henry, went slowly due to material shortages and quarrels among the leaders managing the task. Nevertheless, Tilghman managed to do a more credible job on the construction of Fort Donelson, which lay on dry ground and commanded the Cumberland River.

On February 6, 1862, an army under Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and gunboats under Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote attacked Fort Henry in a surprise winter campaign. Tilghman was still inside Fort Henry when the attack began, having decided to share the fate of the garrison as a rear-guard while the bulk of his forces escaped down the 12-mile road to Fort Donelson. Ironically, the attack on Fort Henry on February 6th need not have taken place at all, since the fort flooded completely on February 8th due to the rising river.

After the surrender of Forts Henry and Donelson, Tilghman joined General Simon B. Bucker in captivity at Fort Warren in Boston. The Union released him on August 15, 1862 in exchange for Union General John F. Reynolds, a future hero of Gettysburg, who had been captured during the Seven-Days battles.

Returning to the field in the fall of 1862, Tilghman became a brigade commander in Mansfield Lovell’s division of Earl van Dorn’s Army of the West. Shortly thereafter, General Lovell was recalled and his division passed to William Loring. The division joined Pemberton’s Army of the Mississippi for the defense of Vicksburg.

At the Battle of Champion Hill, May 16th, 1863, Tilghman led his brigade of Mississippians. Loring was out maneuvered by McClernand and forced to retreat. Assigned to be the rearguard, Tilghman was killed by a shell fragment which passed completely through his chest. The remaining brigades of the division escaped the Federal encirclement.

After his enlistment with the Confederate Army, Tilghman’s wife, Augusta, had moved to Tennessee. She returned to New York City after the war. At her orders, Tilghman was removed from his Mississippi grave and placed in a tomb at Woodlawn Cemetery in New York City. Augusta died in 1898, and was buried next to the general.

Opinions on Tilghman’s actions to prepare the forts vary among commentators. Although all admit that remaining with the Fort Henry artillerists to the bitter end was an act of gallantry, some have stated that he was dilatory in their construction and as a result, the forts were vulnerable when Grant attacked. Others state that allowing himself to be captured at Fort Henry created a vacuum in leadership which allowed the rapid investment of Fort Donelson and resulted in the indecisive John Floyd coming into command at Fort Donelson.

In my opinion, both of these criticisms are unfair. It is true that the forts were not complete by the time that Grant launched his campaign. However, to blame Tilghman for their lack of readiness in the face of materiel shortages and poor siting by his predecessors is unfair. Tilghman had initiated the construction of Fort Heiman on higher ground across the Tennessee to replace Fort Henry but his men had not completed it before Grant’s surprise winter campaign. The criticism detracts from the boldness of General Grant specifically to avoid allowing the Confederates time to complete the fortifications.

The argument that Tilghman left a vacuum of leadership between the fall of Fort Henry and the investment of Fort Donelson may have some merit but ignores the presence of General Bushrod Johnson among the forces defending the Henry-Donelson line and the fact that until reinforcements arrived at Fort Donelson, the Confederates had only two brigades available to oppose Grant’s seven larger brigades.